Detecting gravitational lenses: from astronomical survey to hubble

In 2019 we initiated a collaboration between my lab and Tucker Jones’s lab in UC Davis Physics. The idea was to detect gravitational lenses in a real (new) astronomical survey, the Deep Lens Survey (DLS), and then use these detections to actually confirm the discovered lenses on telescopes like the Keck observatory. We found that this was way harder than testing machine learning methods on benchmark datasets.

A gravitational lens occurs when the light from a background source like a galaxy bends around a massive object, forming a lens in space. However, because they are rare and this is a new survey, we are in a zero-shot learning situation, but we also have distributional shift because any training data from another survey will look completely different. We solve this by forming realistic simulated lenses, and pairing this with semi-supervised learning to transfer to the DLS.

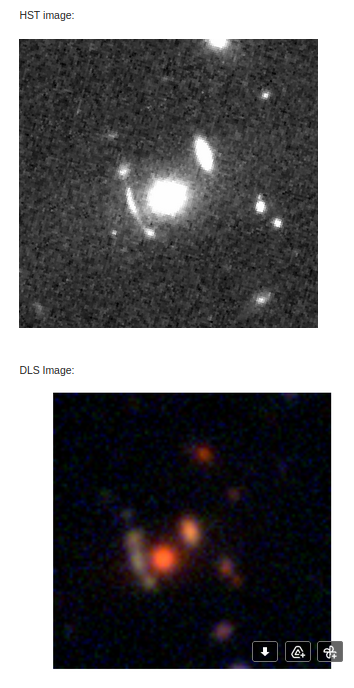

Non-lens (left), simulated lens (center), real lens (right)

At no point do we use the real lenses to train or validate our model, rather only in testing the handful of trained models do we get to see our real lenses. The devil is in the details however, and the success of our method relied on a lot of engineering and method selection. The key components of our best method were

- Smart data augmentation

- MixMatch: our semi-supervised learner

- GANs

- and of course really good simulated lenses (based on ray optics simulation).

You can see our final work in the recent paper which was published in AIStats.

Stephen Sheng, Keerthi Vasan GC, Chi Po P Choi, James Sharpnack, and Tucker Jones. An unsupervised hunt for gravitational lenses. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, pages 9827–9843. PMLR, 2022.

Abstract

Strong gravitational lenses allow us to peer into the farthest reaches of space by bending the light from a background object around a massive object in the foreground. Unfortunately, these lenses are extremely rare, and manually finding them in astronomy surveys is difficult and time-consuming. We are thus tasked with finding them in an automated fashion with few if any, known lenses to form positive samples. To assist us with training, we can simulate realistic lenses within our survey images to form positive samples. Naively training a ResNet model with these simulated lenses results in a poor precision for the desired high recall, because the simulations contain artifacts that are learned by the model. In this work, we develop a lens detection method that combines simulation, data augmentation, semi-supervised learning, and GANs to improve this performance by an order of magnitude. We perform ablation studies and examine how performance scales with the number of non-lenses and simulated lenses. These findings allow researchers to go into a survey mostly “blind” and still classify strong gravitational lenses with high precision and recall.

Discovered lenses

We have confirmed two of gravitational lenses that we have discovered, a process that was slowed down by the pandemic lockdowns. The first was confirmed spectroscopically (basically see that it is really really old light) at the Keck observatory. Here is the image from the DLS survey.

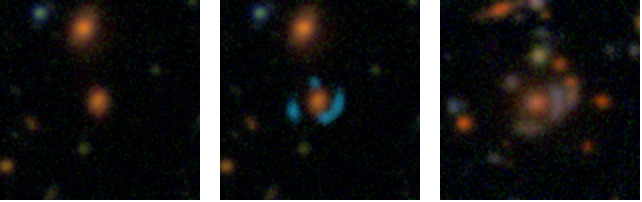

The second lens was also confirmed at Keck, but we were also able to get a glimpse of it on Hubble. We can see the Hubble image (top) and the DLS image (bottom) below.